Abbey, A., Pilgrim, C., Hendrickson, P., Lorenz, S.

The Journal of Primary Prevention

Vol. 18, No. 3

1998

Abstract

A family-based alcohol, tobacco, and other drug abuse prevention program was evaluated. The program targeted families with students entering middle or junior high school. The goals of the program were to increase resiliency and protective factors including family cohesion, communication skills, school attachment, peer attachment, and appropriate attitudes about alcohol and tobacco use by adolescents. The Families In Action program is a structured program which includes six 2-hour sessions, offered once a week for six consecutive weeks to parents and youth. The program was offered to all eligible families in eight rural school districts. Families who chose to participate began the program with lower scores on several protective factors as compared to nonparticipating families. Analyses of covariance controlling for initial differences found several positive effects of program participation at the one year follow-up. The results were strongest for boys. These finding suggest that providing parent and youth with similar communication skills can be an effective approach to substance abuse prevention.

Introduction

The concept of “Checkpoint Parent Education” was contained in the 1986 document “Mental Disability Prevention in Michigan.” This effort was based on the philosophy that there are developmental phases in the life of a family when parents are most in need of and most willing to seek out parenting information and support. These checkpoints are when children are born, when they enter kindergarten, when they enter junior high or middle school and when they enter high school. The first checkpoint program implemented by the AuSable Valley Community Mental Health Services agency (AVCMH), in cooperation with participating schools and county human services councils, was titled “ABC’s for Parents: Assuring Better Children.” It was developed in 1989 to address family prevention issues as children enter kindergarten. Based upon the success of that program, AVCMH implemented the Middle School Checkpoint Parenting Program entitled “Families in Action: Meeting the Challenge of Junior High and Middle School” (FIA), with funding from the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention. In cooperation with participating schools, FIA was designed to meet the substance use prevention needs of families as children enter the adolescent years. The current article describes the underlying theory behind the FIA program, its structure and research supporting this approach.

Theoretical Model

Numerous theories have been developed to explain adolescent substance use (Kandel, 1980; Needle, Lavee, Su, Brown, & Doherty, 1988; Newcomb, Maddahian, Skager, & Bentler, 1987; Rhodes & Jason, 1990; Simons, Conger, & Whitbeck, 1988). Hawkins and Lam (1987) argued that a variety of adolescent delinquent behaviors, including substance use, are best explained through a social developmental model which emphasizes the critical role of family, school, and peers in adolescent development. As they mature, youths sequentially “bond” or “attach” to parents, school, and peers. Positive familial attachment encourages bonding with school and prosocial peers. These positive bonds with family, school, and peers, in turn, encourage prosocial behavior and discourage substance use and delinquency (Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992).

Hawkins, Catalano, Jones and Fine (1987) suggested that parents can be trained to modify the behavior of their children. By increasing parents’ skills, parent training can increase school achievement, decrease problem behavior, build the capacity of the family to solve problems, and reduce juvenile crime. By creating successful opportunities for children to interact within the family, setting clear expectations for their children, and in practicing consistent and contingent family management, parents can positively influence their child’s behavior. Hawkins et al. (1992) suggested that children raised in families with low communication and involvement between parents and children are at high risk for later delinquency and drug use. In contrast, positive family relationships appear to discourage youths’ initiation into drug use.

The FIA program was built upon the research by Hawkins and colleagues described above. The FIA program includes modules addressing parent/child communication, positive behavior management, interpersonal relationships for adolescents, and factors which promote school success. Each of these components is designed to increase the attachment between youths and their family, school, and peers.

The FIA program was developed to provide students with more than information about the negative social and physical effects of substance abuse. The focus was on teaching a combination of general life skills and social resistance skills and providing opportunities to practice these skills (Abbey, Oliansky, Stilianos, Hohlstein, & Kaczynski, 1990; Botvin, Baker, Dusenbury, Botvin, & Diaz, 1995; Botvin & Botvin, 1992). In addition, the FLA program targeted the entire family, as suggested by Hawkins and colleagues (1987). Another facet of the program was to make families aware of community and school resources which could provide additional assistance if necessary.

The decision to target all families in the specified age group was based upon research conducted by Hawkins et al. (1987). They suggested that if only high-risk families are singled out for intervention, there will be a stigma attached to program participation. his stigmatization will reduce the program’s ability to attract families in need of assistance. In addition, the inclusion of well-functioning families in the program provides high-risk families with models of desirable family interaction and communication.

Hypotheses

The goals of the FIA program were to increase resiliency and protective factors within high-risk youths and their parents in order to reduce the likelihood that youths would use alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs (ATODs). Specifically, the FLA program sought to significantly increase amongst participating students: 1) positive attachment to their family; 2) positive attachment to their school; 3) positive attachment to their peers; 4) willingness to talk with counselors when needed; and 5) appropriate attitudes toward the use of ATODs by minors. For parents, the goals were to increase: 1) positive attachment to their family; 2) time spent in enjoyable family activities; 3) involvement in their child’s school; 4) willingness to talk to family or school counselors when needed; and 5) appropriate attitudes toward the use of ATODs by minors. It was hypothesized that those students and parents who participated in the FIA program would show greater increases in these domains over the course of a year as compared to a group of nonparticipating students and parents.

A few substance abuse prevention programs have found differential effects for boys and girls (Moskowitz, Schaps, Schaeffer, & Mahin, 1984), thus gender differences in program effectiveness were considered.

Program Description

The FIA program is a structured program designed for parents and their children who are entering junior high or middle school. The program was offered each fall, winter, and spring in eight participating junior high and middle schools in a three-county area of rural northeastern lower Michigan. The program was comprised of six 2.5-hour sessions, offered once a week for six consecutive weeks. Sessions were typically held in school classrooms on weekday evenings. Group size consisted of anywhere from five to 12 families.

Two to three times each year, FIA graduates and other families within the target age group were invited to participate in evening family reunions. These typically included a pizza dinner, social time and an education and skill-building session. Topics were selected based upon the suggestions of program graduates. The entire family was encouraged to attend, with child care provided for siblings who were too young to benefit from the structured program.

The FIA curriculum was adapted from Dr. Michael Popkin’s (1990) textual and video program “Active Parenting of Teens.” Popkin’s program was designed only for parents, therefore, FIA program staff developed a student curriculum and a student handbook. Program staff also developed an audiotape version of the parent handbook for parents with poor reading skills or eyesight and activities and group exercises appropriate for their population. Sessions 1 and 2 focused on positive thinking and how to use positive rather than negative strategies to reach behavioral goals. Sessions 3 and 4 taught positive communication skills and natural and logical consequences for one’s actions. Session 5 focused on school success. Session 6 dealt with the avoidance of ATOD use by youth.

The FIA program targeted multiple domains: the individual, family, peer, school and community. These components are described below.

Individual domain. The FIA program provided skill-building opportunities for parents and youth to increase interpersonal communication skills, basic knowledge of adolescent development, and avenues to school success. The students’ segments focused on developing responsible and cooperative behavior in all aspects of their lives. For example, the students were taught that growing up involves making choices and that with these choices come consequences.

Family domain. The FIA program utilized a family systems approach, providing opportunities for families to attend the program and learn skills together. Each of the sessions included time during which parents and youth met in separate groups and time during which all family members met together. Even during those times in which parents and adolescents were separated, the skill-building sessions were designed to teach similar skills utilizing age-appropriate materials. The majority of the skills were taught in the context of family life. At each session, families were provided with family enrichment activities to complete during the week. These home activities formed the basis for the following week’s “Share and Tell” component. The program also provided sibling care for other children in the family who were not in the target age group, thus making it more likely that families would be able to attend sessions together.

The family systems approach allowed the family to learn the same skills and to have a common conceptual basis from which to function after leaving the program each week. For example, in Session 3, participants were taught to express their feelings through the use of “I feel . . .” messages. During the next week, students and parents were encouraged to practice these “I” messages on one another. Opportunities for practice, role play and discussion between parents and students opened channels of communication.

The program used a positive approach to family enrichment. Rather than being a program which was publicized as preventing something negative (substance abuse), it was marketed as an opportunity for families to enhance their interactions. The program was consistently and conscientiously promoted as something that all families could benefit from rather than a program that some families “needed.” Participation was based upon attraction rather than coercion.

School domain. The FIA program was held in partnership and cooperation with participating schools. Publicity about the program was regularly (although not solely) sent out through the schools, on school letterhead, and with school personnel’s signatures. Sessions were held in the school classrooms and libraries, providing an opportunity for parents to have a warm, nurturing experience in the school environment. The fifth session focused on the topic of school success, and school personnel attended. Parents had the opportunity to assess their own behaviors in relationship to the school and were given information about how they could become involved in a positive way with their young person’s school career.

Students met in a separate group during this phase of the program. They also learned about opportunities for school success through social, academic, behavioral, and other avenues. In addition, they set school-related goals for themselves during this session. This component of the curriculum was developed in cooperation with school personnel.

Peer domain. The communication skills that parents and youth were taught to use with each other were also useful to youth in their peer interactions. Through the team-building activities included in the youth sessions, students learned how to relate to peers in positive ways. Students also practiced effective peer pressure resistance skills and the avoidance of ATODS. Students who attended the program signed a “no use of ATODs agreement” and discussed logical consequences for violation of this agreement. Thus, student participants developed a peer group which had made a commitment to “zero tolerance.”

Community domain. The program was provided in each school district by persons from the community served by that school. Parent group leaders, student group leaders and other program staff were recruited based upon recommendations from the school that they were persons of sound character and good reputation in the community. In rural cornmunities, everyone knows one another and families would not attend if the group leader had a negative reputation. Parent group leaders were recruited on the basis of having had nurturing parenting experiences and being able to lead group discussions in a nonjudgmental fashion. Student group leaders were recruited on the basis of having a reputation for treating youth with respect, knowing how to make learning fun, and having good behavior management skills. In some communities, the most effective staff were professionals who worked in the school or in a human service agency. In other communities, the most effective staff were individuals with strong community ties and service experience who did not necessarily have a college education. The success of an individual or a certain “type” of individual depended upon the social norms and expectations within the given community. In some of these rural communities a college education and professional training was valued; in others they were viewed with suspicion.

Program staff made presentations at human services organizations, civic groups, and churches so that community leaders would be aware of the program and would encourage their eligible members to participate. Also, the business community contributed by: 1) displaying program posters in their windows; 2) providing door prized for program participants; 3) providing incentives for evaluation activities; and 4) donating program T-shirts.

The development of a community norm for FLA participation was a major goal of the program. Families from all walks of life participated. This made it possible to reach families without labeling them as “high-risk” families. The development of a community norm for program participation also helped to create a critical mass of families within the community who subscribed to similar standards of behavior for children and who valued their students’ success in school.

The FIA program regularly published a quarterly newsletter containing relevant parenting information designed to reinforce topics taught in the structured sessions. It also contained information about upcoming programs and family reunions. This was sent to all program graduates and to other families with students in the target age group. It functioned simultaneously as a marketing tool and as a method for reinforcing what graduates had learned in the program.

Method

Participants

The FIA program was eventually introduced into eight schools; the evaluation focused on the four schools in which it was first implemented. During the 1993 school year, 58 students and 61 parents from these four schools completed the program. The comparison group was comprised of 510 students and 443 parents who completed the baseline evaluation survey (described below) but did not choose to participate in this voluntary program. As noted in previous sections, the targeted grade for FLA participation was the entry school year: 6th grade for middle schools and 7th grade for junior high schools.

Demographic profile of the communities. According to U.S. Census data (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1991), the largely rural area in which the evaluation was conducted had 39,344 residents; there were 7,120 children enrolled in school. A primary industry was tourism. The majority of the people in this rural area did not own or work their own farm, rather they worked as laborers or in service jobs. Ninety-six percent of the population was Caucasian. Twenty-one percent of the children in the county lived below the poverty line.

Procedure

Baseline and one-year follow-up. In the fall of the 1993 school year, a baseline survey was administered to parents and students in the four evaluation schools in the grade targeted for the FIA program The same survey was administered in the fall one year later. FIA participation was voluntary, thus at the beginning of the year it was not known which families would choose to participate in the program. Identification numbers were assigned to students and parents so that it was possible to distinguish between FIA participants and nonparticipants and to link baseline and follow-up surveys. Those families which participated in the program became the treatment group and those that did not participate became the comparison group.

Students completed their surveys in school, and a make-up day was provided for students who were absent. Passive parental consent was obtained with approval of the Wayne State University Human Investigations Committee and the schools. Students placed their surveys directly into an envelope, which was then sealed by one of the students in order to increase their sense of confidentiality. Ninety-six percent of the students completed a baseline survey.

The one-year follow-up response rate was 71% for students in the comparison group and 74% for student program graduates. The majority of the attrition from the baseline to the one-year follow-up was due to students moving out of the school district. The student survey refusal rate was less than 5% at each school. Students who completed a one-year follow-up survey had higher grade point averages (M = 2.92) than those who did not (M = 2.62), F(1,494) = 9.78, p < .001. They also had fewer absences (M = 3.99) than those who did not return a one-year follow-up (M = 5.46), F(1,501) = 8.64, p < .003. There were no significant differences on any of the outcome measures.

Parents were mailed surveys and returned them in prestamped, pre-addressed envelopes which were sent directly to the evaluators. A parent was defined as the mother, father, step-parent or an adult guardian of the student. At least one parent in 54% of the households completed a baseline parent survey, with females (61%) accounting for more surveys than males (39%). The one-year follow-up response rate was 38% for parents in the comparison group and 69% for parent program graduates. Again females (65%) returned more surveys than did males (35%).

Parents who returned a one-year follow-up survey reported higher levels of education (M = 13.08 years) than those who did not (M = l2.7 years), F(1,441) = 3.86 p < .05. Those who returned a survey also had slightly fewer children (M = 2.28) than those who did not (M = 3.16), F(1,441) = 3.88, p < .05. As with students, there were no significant differences on any of the outcome measures.

Students and parents who returned the surveys were given a small incentive. The school principal was allowed to select the incentive which she or he thought would be most appropriate for that school’s population. Students’ incentives included a free brownie at lunch or a fast food french fries and pop coupon. Parents’ incentives included free milk coupons or a lottery for $50.00.

Participants only: Pretest, posttest, and 10-week follow-up. In addition to a baseline and one-year follow-up survey, program participants completed a pretest (the first night of the program), a posttest (six weeks later during the last night of the program), and a 10-week follow-up survey (mailed one month after the program ended which was 10 weeks after the pretest). The pretests and posttests were administered at the program; the 10-week follow-up was mailed to participants with a pre-addressed, prestamped return envelope. Incentives comparable to those described above were given to participants who returned the 10-week survey. These three surveys included the same questions that were on the baseline and one-year follow-up. The purpose of these additional data points was to examine the short-term effects of program participation. These additional measurements were not attempted for comparison group members because of the time burden. Response rates for FIA graduates on the pretest, posttest and 10-week follow-up were 94%, 88% and 73%, respectively.

Program attrition. Seventy-one percent of the participants who attended Session I of the program graduated from the program (a graduate was defined as someone who attended at least four out of the six sessions). Pretest comparisons were made between parent and student program graduates and those who dropped out of the program on 22 measures. The only significant difference was that parent dropouts reported less family activities (M = 2.90) than did parent graduates (M = 3.12), F(1,82) = 5.45, p < .02. Parents and students who started the program but did not complete it are not included in either the participant or nonparticipant group.

Measures

Most concepts were measured with multi-item scales that were included for both parents and students at each time point. A few measures were only asked of one age group and one measure was only included for program participants. Details about the instruments are described below. The Cronbach coefficient alphas were of comparable magnitude at the baseline and one-year follow-up, so they are only presented for the baseline measures.

Family cohesion. Family cohesion was measured with the 9-item cohesion subscale from the Family Environment Scale (Moos, 1986). The scale has a true/false response option and all items were averaged into a single family cohesion score. The cohesion scale assessed the “degree of commitment, help and support family members provided one another” (Moos, 1986, p. 2) and a higher score reflected greater family cohesion. Cronbach coefficient alphas for the students and parents on the cohesion scale were alpha = .81 and i>alpha = .80, respectively.

Shared family activities. For parents only, the amount of time spent in family activities was assessed with an 8-item scale (Sebald & Andrews, 1962). A sample item asked “How often do you participate with your child in activities or hobbies?” The scale provided a 4-point response scale with options ranging from never to often. The 8 items were averaged for an overall family activities score (alpha = .88).

School attachment. School attachment was measured with a 10-item scale from the Effective School Battery (Gottfredson, 1984). The Attachment to School subscale uses a 2-point response option and assesses whether respondents “like” or “don’t like” the student’s school, teachers, principal, counselors and classes. The items were averaged to obtain a global school attachment score for both students and parents (alpha = .77 and alpha = .64, respectively).

Participation in school activities. A school activities scale was developed by the evaluation staff. Students and parents were asked to report in a yes/no format whether or not they were involved in different activities at the child’s school (e.g., member of a club or team, attended a PTA meeting). Students reported on three school activities and parents reported on five school activities. An average score was computed for both.

Peer attachment. For students only, perceptions of friends’ supportiveness was measured with a 15-item subset of the Inventory of Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). The inventory uses a true/false response scale and the items were averaged to obtain an overall peer attachment score (alpha = .88).

Experience with counselors. The evaluation staff developed a 3-item scale which assessed whether or not the student or parent had talked with a psychologist, a social worker or a school counselor. An average score was calculated.

Curriculum knowledge. An FIA curriculum knowledge scale was developed by the evaluation staff to assess the extent to which participants learned the information presented in the program. This measure was only included for parent program participants at the pretest, posttest, and 10-week follow-ups. This was a 6-item multiple choice test; one item was included for each session of the program. An average curriculum knowledge score was computed.

Appropriate attitudes toward alcohol and tobacco use by minors. Rates of ATOD use are very low among sixth and seventh graders (Botvin et al., 1995; Dielman, Shope, Leech, & Butchart, 1989; Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 1993). Thus, if ATOD use is the central outcome measure it is difficult to find significant effects because scores are highly skewed. Therefore, attitudes about adolescent alcohol and tobacco use were assessed for this study rather than actual use. Past research indicates that youths’ attitudes about substance use are highly predictive of later use (Hawkins et. al., 1992; Johnston et al., 1993; MacKinnon et al., 1991). Earlier needs assessments had indicated that rates of illicit drug use were very low in these communities; alcohol was the primary drug used by youth. Therefore, the measure focused on attitudes about alcohol and tobacco.

Both the 5-item alcohol and 2-item tobacco attitude scales were created by adapting items from the “Parents” scale in Program Evaluation Handbook: Drug Abuse Education (IOX, 1988). The scales provided a 4-point response option ranging from definitely yes to definitely no. Students’ questions were phrased in terms of their friends (e.g., “Would you be upset if your friend took you to a party where alcohol was being used?”). Parents answered parallel items about their child’s use of alcohol and tobacco (e.g., “Would you be upset if your teenager got drunk on a special occasion like a graduation party or New Year’s Eve?”). The Cronbach coefficient alphas were .81 and .78 for students’ and parents’ alcohol attitudes; they were .83 and .72 for students’ and parents’ tobacco attitudes.

The legal drinking age in Michigan is 21 years of age. Students and parents were also asked at “What age do you think that it is O.K. to drink more than a sip of alcohol?”

Demographic and school information. Students’ grade point average and number of school absences were collected from the school. Students reported their age on the survey. Parents’ surveys included questions about their education, number of children, and annual household income.

Process Evaluation

If a program is not faithfully implemented by staff, then it has little chance of producing statistically significant outcome findings that can be replicated. The evaluation staff made frequent observations of parent and student group sessions. Overall, implementation was very good. Group leaders followed the curriculum and handled discussion questions and role plays well. The most frequent problem was going past the allotted time because activities took longer than anticipated.

Results

Comparability of Program Participants and Comparison Group Members at Baseline

A quasi-experimental research design was used (Cook & Campbell, 1979). This was a voluntary program, thus it was particularly important to determine the comparability of parents and youth who chose to participate in the program and those who did not. One-way analyses of variance (Program Graduate versus Nonparticipant) were conducted for all the baseline measures for students and parents who completed the baseline and one-year follow-up survey.

Students’ findings. As can be seen in Table 1, students who graduated from the FIA program had at baseline significantly less appropriate attitudes towards adolescent tobacco use, lower scores on family cohesion, lower school attachment and higher rates of talking to counselors than did members of the comparison group. Student graduates also had significantly more school absences and were significantly older than members of the comparison group at baseline. FIA graduates had marginally less appropriate attitudes towards adolescent use of alcohol and lower peer attachment. There were no significant baseline differences for reported “age O.K. to drink alcohol,” school activities or grade point average.

Parents’ findings. For parents, there were three baseline differences between graduates and members of the comparison group. Table 2 shows that parents who graduated from the FIA program had significantly lower scores at baseline on cohesion and had significantly higher rates of talking to counselors. Also, parent graduates had significantly fewer years of education than did comparison group parents. There were no significant baseline differences in appropriate alcohol attitudes, appropriate tobacco attitudes, reported “age O.K. to drink alcohol,” family activities, attachment to their child’s school, school activities, family income or number of children in the home.

Effects of Program Participation at the One-Year Follow-up

Because of the baseline differences, all comparisons of the one-year follow-up scores for program graduates and comparison group members controlled for initial differences between groups on the baseline survey. Baseline scores were treated as a covariate so that change from baseline to follow-up was compared for the two groups, and therefore only adjusted means are presented below. Also, demographic information from parents (education, number of children and income) and students (age, absenteeism and grade point average) were treated as covariates. Inclusion of the demographic information as covariates did not change any of the program findings, thus they were excluded from the analyses presented below.

Students’ results. A series of one-way analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to examine program effects. There were four significant main effects. A series of 2 (Male, Female) x 2 (Program Graduate, Nonparticipant) ANCOVAS was also conducted to detemiine whether the program effects were comparable for boys and girls. There were approximately an equal number of girl and boy graduates (N = 22 and N = 21, respectively) and girl and boy comparison group members (N = 192 and N = 171, respectively).

Three significant program effects were moderated by gender (appropriate alcohol attitudes, school and peer attachment), therefore, only the interactions are reported below. The main effect of talking to counselors was not moderated by gender. Controlling for baseline scores, student graduates (M = .40) were more likely than nonparticipants (M = .25) to talk to a counselor at the one-year follow-up, F(1,399) = 8.28, p < .004.

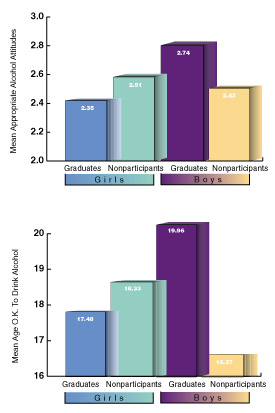

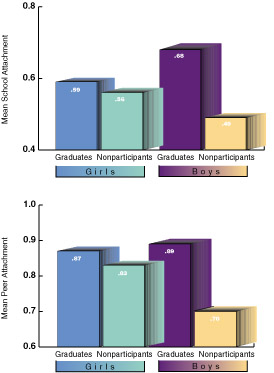

Significant interactions between program participation and gender were found for four student measures. Controlling for baseline scores, at the one-year follow-up boy program graduates scored significantly higher than did boy nonparticipants on: appropriate attitudes towards alcohol, age reported that it is “O.K. to drink alcohol,” school attachment and peer attachment (see Figures I & 2). These four program effects were not significant for girls.

Parents’ results. As with the students, a series of one-way ANCOVAS was conducted for all outcome measures with parents. When controlling for baseline scores, parent graduates at the one-year follow-up reported more involvement in school activities than did nonparticipants, F(1,201) = 9.93, p < .002; M = .65 and M = .54, respectively. Parent graduates also reported more involvement in family counseling (M = .52) than did nonparticipants (M = .32), F(1,201) = 10.96, p < .001 controlling for baseline scores. No other significant effects were found for parents. Most parent program participants were women (79% female; 21% male), thus gender of participant effects could not be examined for parents.

Short-Term Effects for Program Graduates

Students’ results. To examine the short-term effects of program participation, paired t tests were conducted using the pretest, posttest and 10-week follow-up data which was collected only for program participants. For students, effects were found on two of the nine measures. Student graduates had significantly higher peer attachment scores at the six-week posttest 9 (M = .76) than at the pretest (M = .70), t(43) 2.16, p < .04. This effect was not significant at the 10-week follow-up.

Fig. 1. The figure shows significant program by gender interactions at the one-year follow-up when controlling for baseline scores. Displayed are the adjusted mean scores on the one-year follow-up for appropriate alcohol attitudes (top) and reported “age OK to drink alcohol” (bottom), F(1,310) = 9.03, p < .003; F(1,400) = 4.99, p < .03, respectively.

Students’ attitudes about adolescent alcohol use became significantly less socially appropriate from the pretest (M = 3.03) to the posttest (M = 2.74), F(43) = 3.1 1, p < .003. When boys’ and girls’ data were analyzed separately, this effect was found to be significant only for girls (M = 3.05 pretest; M = 2.59 posttest), t(2 1) = 4.3 1, p < .001 This is presumed to be a maturation effect, rather than a program effect, because girl program participants did not score significantly worse over time than did the comparison group participants (see Figure 1).

Fig. 2. The figure shows significant program by gender interactions at the one-year follow-up when controlling for baseline scores. Displayed are the adjusted mean scores on the one-year follow-up for school attachment (top) and peer attachment (bottom), F(1,388) = 4.72, p < .03; F(1,398) = 3.71, p < .05, respectively.

Parents’ results. Significant effects were found for three of the nine parent measures. Parent graduates had significantly higher family cohesion scores at the six-week posttest (M = .75) than they did at the pretest (M = .66), t(53) = 2.89, p < .006. This effect did not last until the 10-week follow-up.

Significant effects for the age parents thought it was “O.K. to drink alcohol” were also found. At the posttest (M = 20-55) and at the 10-week follow-up (M = 21.09), parents reported a higher age than they did at the pretest (M = 20.10), t(40) = 2.42, p < .02 and t(34) = 2.13, p < .04, respectively.

Significant effects were also found for the curriculum questions, which assessed knowledge of key program concepts. At the posttest (M = .62) and 10-week follow-up (M = .64) parents had significantly higher scores than they did at the pretest (M = -43), t(47) = 5.64, p < .001 and t(34) = 5.16, p < .001, respectively.

Discussion

The Families In Action program is a unique prevention program because it focuses on a multitude of domains as a means of preventing ATOD abuse. Specifically, the individual, family, school, peer and the community domains were incorporated into the FIA program. By including both students and parents in the program and teaching them comparable skills, changes can begin to occur within the family unit, which then facilitate positive changes in the adolescent toward school, peers, and substance use.

The program provides general life skills for both parents and students. Parents and students learn new communication skills which enable them to better handle conflicts and decisions in their personal lives. Students learn to use these new skills in parent, school, and peer interactions. Parents are taught to use their new life skills with their children, spouse, and co-workers.

The results indicated several positive program findings for students and parents. Girl and boy program graduates were more willing to seek counseling services at the follow-up. Program participation was more beneficial for boys than for girls. Boy graduates had higher school and peer attachment, more appropriate attitudes about alcohol, and believed that alcohol should be consumed at an older age as compared to boy nonparticipants. Teachers and professionals in the program area were interviewed regarding their perspective on why the program had stronger effects for boys than for girls. They noted that middle/junior high school girls often date older boys who are in high school. It is possible that some of the girls taking the program were too developmentally advanced for this particular program. The focus of the program was on preventing the initiation of ATOD use and some of the girls may have already been involved with older boys who are using substances. Another possibility is that boys related to the characters in the video segment of the program more than girls did. Students taking the program have commented that the boy characters in the video were “cool” while one of the primary girl characters was perceived as being “whiny.” The gender effect should be interpreted with caution because in a second cohort all program effects were significant for both boys and girls (Abbey, Pilgrim, Hendrickson, & Lorenz, in preparation). One possible explanation for the non-replication of the gender effect is that program staff made additional efforts to engage girl participants. Thus, the program became more appropriate for both genders. In addition, the second cohort recruited higher functioning students.

Parents who graduated from the program reported an increase in activities at their child”s school and an increase in talking with counselors as compared to nonparticipants. Although these were small effects, program staff view these as important and promising. It is unrealistic to expect that a six-week program can completely turn around lifetime habits and beliefs about parenting, communication, and discipline. If program participation makes parents more willing to seek out additional sources of information, support, and advice and to become more involved in their child’s school, over time these families may experience additional positive changes. Follow-ups of three to five years may be necessary to identify the full impact of this type of program on family dynamics and ATOD use.

Some short-term program effects were found for parent graduates only: greater curriculum knowledge, higher family cohesion and an increase in the age considered appropriate for alcohol consumption. It is possible that if the program was of longer duration or if a booster session was provided the following year, that these short-term effects would have persisted. At the conclusion of the program, participants frequently stated that they wished it would continue longer. However, when program staff tried to arrange for on-going parent support groups, these were poorly attended. Finding ways to encourage busy families to make a long-term commitment to family development is a challenge for all voluntary programs. As noted in the previous paragraph, it may be unrealistic to expect this program alone to change families unless it encourages them to seek out additional services.

There are several aspects of the study design which encourage caution in interpreting and generalizing the results. Participants were not randomly assigned to conditions so initial differences between groups may have affected the findings, although analyses were conducted controlling for baseline differences between groups on the outcome measures and demographic variables. Although families from all socioeconomic backgrounds participated in the study, on average, those that chose to participate were more “needy” than those who chose not to participate in the program. owever, such pre-existing differences between groups makes it more difficult to find significant results (Cook & Campbell, 1979). In addition, program participants completed the questionnaire more times than did nonparticipants so there may have been a testing effect (Cook & Campbell, 1979). There was, however, at least a four month gap between the 10-week and the one-year follow-up so it is unlikely that participants remembered the ir previous responses. This program was conducted in a rural, primarily Caucasian, low-income area in the Midwest. Analyses of an additional cohort of data from this program also show a number of significant program effects (Abbey et al., in preparation). Replication of the program is also needed with other populations in order to determine the generalizability of the results.

Given these cautions about the need for replication, this study’s findings have a number of implications for substance abuse prevention programming. Primary prevention programs benefit from strengthening youths’ attachment to parents, school staff, and prosocial peers before students are at the age where experimentation with alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs is common. In the communities where this program was examined, it is very common for parents to provide youth with alcohol for their parties. Changing such a community norm is not easy and takes many years. By providing youth and their parents with a peer group that had signed a “zero tolerance” pledge, the FIA program created a positive peer group for families uncomfortable with underage alcohol consumption.

Some practical issues associated with conducting prevention programs in a rural community involve the large geographic distances between people, the lack of transportation, and the lack of recreational activities for youth. A strong sense of self-reliance and privacy also made it difficult for many people to attend a parenting program; they seemed to feel that they should be able to handle any difficulties themselves. Also, in a rural community there is less anonymity from others than in an urban area. Occasionally, people would opt out of the program once they heard about who else had registered because they did not like or want to associate with them. These issues can also arise in urban and suburban areas, however, they appear to be more salient in small towns.

Parents and youth reported enjoying both the times during the program when they were apart and the times when they were together. Each age group had some issues it wanted to discuss and work through without being heard by the other generation. Each age group also enjoyed the opportunity to begin practicing some of the skills with each other in the safety of the group. The opportunity to come back each week and discuss with the group leader and each other what had worked at home and what had not was also viewed as beneficial. There are many programs designed to teach parenting skills to parents; the FIA program is unique in its emphasis on teaching the same skills to parents and youth. Changing communication and discipline styles should be more effective when the entire family understands the process. As one girl graduate reported: “We have all learned how to communicate better and therefore we get along better.”

It is very difficult to get families to make a commitment to parent education. This program was successful because of its focus on community involvement and ownership. As one Superintendent of schools stated: “Seeing school personnel, agency professionals, parents and children working together toward better communication and school/home relationships is gratifying.” Schools were given a great deal of control in determining how the program would be staffed and when it would be offered. Community groups were informed about the rogram and asked to help support it. Store owners, teachers, and program graduates proudly wore FIA T-shirts in order to advertise the program and show their support. All the group leaders and childcare workers were hired from the community. Replication in another community might look somewhat different, because other communities may have different needs. What is important is to involve the community from the start in the planning and implementation of prevention programming.

Acknowledgments

This program and evaluation were supported by a grant from the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (6 H86 SP03080-05). The authors wish to express their gratitude to the parents, students and school staff in Iosco, Ogemaw, and Oscoda counties who contributed to the program’s success. Also, many special thanks are extended to the Families In Action staff and participants who were essential to the program. Portions of this paper were presented at the 1996 National High Risk Youth Learning Community Workshop, Division of Demonstrations for High Risk Populations, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, March 26-28, 1996, Arlington, VA.

References

Abbey, A., Oliansky, D., Stilianos, K, Hohlstein, L A., & Kaczynski, R. (1990). Substance abuse prevention for second graders. Joumal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 11, 149-162.

Armsdcn, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their psychological well-being in adolescents. Journal of Adokscence, 16, 427-454.

Botvin, G. B., Baker, E., Dusenbury, L, Botvin, E. M., & Diaz, T. (1995). Long-term follow-up results of a randomized drug abuse prevention trial in a white middle-class population. Journal of the American Medical Association; 273, 1106-1112.

Botvin, G. J., & Botvin, E. M. (1992). School-based and community-based prevention approaches. In J. H. Lowinson, P. Ruiz and K B. Mflhnan (Eds.), Substance abuse: A comprehensive textbook (pp. 910-927). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

Cook, T.D. & Campbell, D.T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Chicago: Rand McNally. Dielman, T.E>, Shope, J. T., Leech, S.L., & Butchart, A.T. (1989). Differential effectivenes of an elementary school-based alcohol misue prevention program. Journal of School Health, 59, 255-263.

Gottfredson, G. (1984). The effective school battery. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources Incorporated.

Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., & Miller, J. Y. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 64-105.

Hawkins, J. D. & Lam, T. (1987). Teacher practices, social development, and delinquency. Newbury Park, California: Sage.

Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., Jones, G. & Fine, D. (1987). Delinquency prevention through parent training: Results and issues from work in progress. In J. Q. Wilson and G. C. Loury (Eds.), From Children to Citizens, Volume III, Families, Schools, and Delinquency Prevention. New York: Springer-Verlag.

IOX Assessment Associates. (1988). Program evaluation handbook. Drug abuse education. Los Angeles: Author.

Johnston, L D., O’Malley, P. M., & Bachman, J. G., (1993). National survey results on drug use from Monitoring the Future study, 1975-1992. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Kandel, D. B. (1980). Drug and drinking behavior among youth. Annual Review of Sociology, 6, 235-285.

MacKinnon, D. P., Johnson, C. A, Pentz, M. A., Dwyer, J. H, Hansen, W. B., Flay, B. R., & Wang, E. Y. 1. (1991). Mediating mechanisms in a school-based drug prevention program. Health Psychology, 10, 164-172.

Moos, R. (1986). Family environment scale – Form R (2nd edition). Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Moskowitz, J. M., Schaps, E., Schaeffer, G. A., & Malvin, J. H. (1984). Evaluation of a substance abuse prevention program for junior high school students. The International Journal of the Addictions, 19, 419-430.

Needle, R. H., Lavee, Y., Su, S, Brown, P., & Doherty, W. (1988). Familial, interpersonal, and intrapersonal correlates of drug use: A longitudinal comparison of adolescents in treatment, drug using adolescents not in treatment, and non-drug-using adolescents. The International Journal of the Addictions, 23, 1211-1240.

Newcomb, M. D., Maddahian, E., Skager, R. & Bentler, P. M. (1987). Substance abuse and psychosocial risk factors among teenagers: Associations with sex, age, ethnicity, and type of school. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse, 13, 413-433.

Popkin, M. (1990). Active parenting of teens. Marietta, GA: Active Parenting Inc.

Rhodes, J. E., & Jason, L A. (1990). A social stress model of substance abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 58, 395-401.

Sebald, H. & Andrews, W. H. (1962). Family integration and related factors in a rural fringe population. Journal of Marriage and Family, 24, 347-351.

Simons, R. L, Conger, R. D., & Whitbeck, L B. (1988). A multistage social learning model of the influences of family and peers upon adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Drug Issues, 18, 293-315. U.S. Bureau of the Census. (1991). 1990 census of population & housing. Washington, DC; U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census.